One of the greatest distractions available when studying a computer-based medium is the computer. And the computer is made up of parts. These parts are cool and totally have thesis-based functions. Here’s how to devote as much of your PhD-writing time to them as possible.

Controller

I should have got one of these ages ago. A controller (like this XBOX 360 Controller for Windows) can close the gap between console and PC gaming for ease of use, if you think controllers are easier to use than a mouse and keyboard. They’re not, but whatever. For certain edge cases they’re invaluable: games made with controllers in mind, driving games, and games that have been half-heartedly ported from consoles (this is one of the reasons I only started playing Dark Souls recently). If you don’t have a controller, get one, and then re-play all those games that felt clumsy with a mouse and keyboard.

Procrastiation gain: 2+ weeks.

Joystick

The former go-to input device for computer gaming, the joystick is now more of a specialist device for simulations involving movement of a plane or a spaceship. But as anyone who’s ever tried to land a biplane on a grass runway using a keyboard will tell you, the joystick is still really good at what it does. If you don’t have a joystick, get one, load up a flight sim, and feel like a pro instantly.

Ludomusicology trivia: the book Music in Video Games: Studying Play features a joystick on its cover. Its usefulness to the pictured conductor is doubtful, however, given that the joystick is around the wrong way. I question whether the person who photoshopped the joystick onto the standard book series image has ever played a game.

Procrastination gain: 10 minutes per painfully slow runway approach, up to your boredom threshold. Multiply by 100+ if you own a VR headset and play Elite: Dangerous, because that is without a doubt the most amazing thing out there.

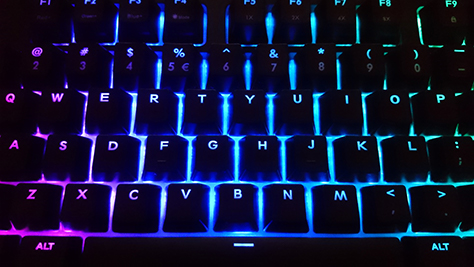

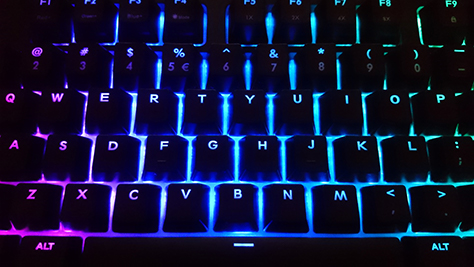

Mechanical keyboard

Making words flow from your hands is pretty cool, so why not do it noisily? Mechanical keyboards are currently hot stuff among computer gamers and typists alike because they feel better, they’re faster, they sometimes let you hold down more keys at once, and there are plenty of configuration options to suit your preferences. Mine has RGB backlighting with various effects; the “rain” effect set to bright green is currently taking me back to when I was 15 and The Matrix was the most awesome thing anybody had ever seen. I’ve also added o-rings to the back of each key to add some refinement to the clackity-clack.

Productivity gain: A few words per minute.

Procrastination gain: Several weeks research, plus extra time waiting for your perfect configuration to be back in stock, plus extra time for modding it when it’s not quite perfect after all.

Headphones

Headphones help you hear things. Mine are old and plastic-squeaky, so moving my jaw/chewing food/speaking to team mates in-game while playing is very loud. Needless to say this is not exactly the kind of thing headphones are supposed to help you hear. However, if you keep your jaw really still you can hear a few things that don’t come through the speakers well, or that would otherwise be muffled by city noise, and you can more clearly observe stereo effects.

Productivity gain: Bonus analytical accuracy.

Procrastination gain: Gosh darn, better play that game again with headphones in case I missed something.

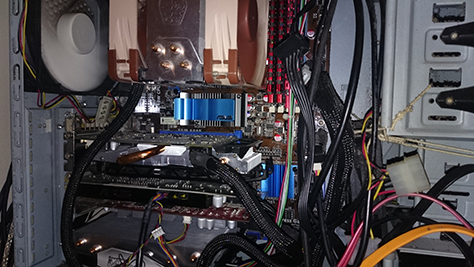

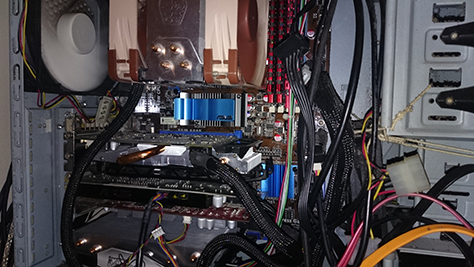

The guts

Computers are complex machines that are made up of building blocks that fit together in standardised ways. Like Lego for nerds. They reward endless amounts of tinkering with either significant additions of functionality, slight performance improvements, or crippling system instability. Which of those you get is pretty much down to the luck of the draw.

Until recently I was running an extra video card in order to do more BOINC science tasks. I also run a nice sound card, and I’ve set up the fans to run extra cool and extra quiet so I can hear said sound card’s beautiful work. But I’ve recently stopped overclocking because it was causing random instabilities. I can’t honestly say I’ve noticed the performance drop, but my nerd cred hurts.

Procrastination gain: 1 hour per part installation or upgrade, plus 6 hours troubleshooting per part installation or upgrade. Also add 1 week per overclocking episode.

Portable computer

For when the computers at uni are also used by undergrads. A great thing to take with you to cafes, libraries and holidays so you can maintain the self-impression of productivity while chilling out. Basically the same as a desktop computer but less tinker-able. However, keen players can install an additional OS or three for multiplicative software maintenance requirements. Also, due to lower hardware resource overheads there’s often more incentive to spend time “optimising” how it runs.

Procrastination gain: An hour a month per OS for software updates. Several hours over the length of the PhD trying to connect to various WiFi networks (I’m looking at you Eduroam).

Printer/scanner/multifunction device

Invaluable for printing articles and for communicating with university departments that haven’t yet digitised any of their paperwork. A mainstay of any home office, the multifunction device (literally: the thing that does all of the things) can also help budding academics to do all of the things. Keen observers will note that I am employing a Hart Industries Make-a-Multifunction Adapter Kit (literally: three pieces of wood and some screws) to minimise device footprint while maintaining full functionality.

Productivity gain: Lets you print and scan things, so you don’t have to trek to a library just to renew society memberships.

Procrastination gain: Kit construction ~1/2 day. Maintenance and upkeep: a few hours whenever you can least spare them (see also Office Space, Mike Judge, 1999).

Raspberry Pi

For when your thesis doesn’t contain enough Linux. Useful for nearly any task, but often less useful for any of those tasks than a device created specifically for that task. But look at them, they’re such cute little computers! And a high cable/LED/footprint ratio, so they look like serious business. I have an RPi model B that runs as a print server and a VPN server, and an RPi 2 than does automated backups of my thesis every hour or so. Both also run BOINC science tasks (very slowly, but they’re always on so at least they’re doing something).

Procrastination gain: If you already know how to Linux, 2+ hours every time you think of something else you can make them do. If you don’t know how to Linux, this is a procrastination goldmine of indeterminate depth — good luck.

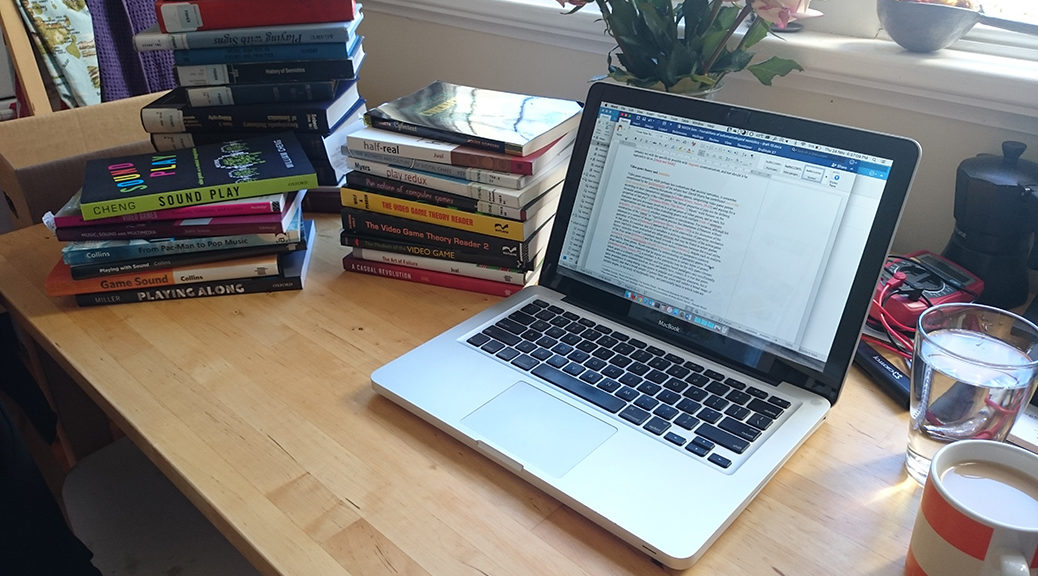

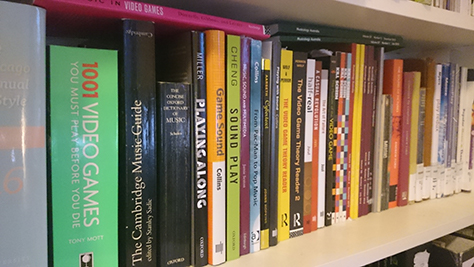

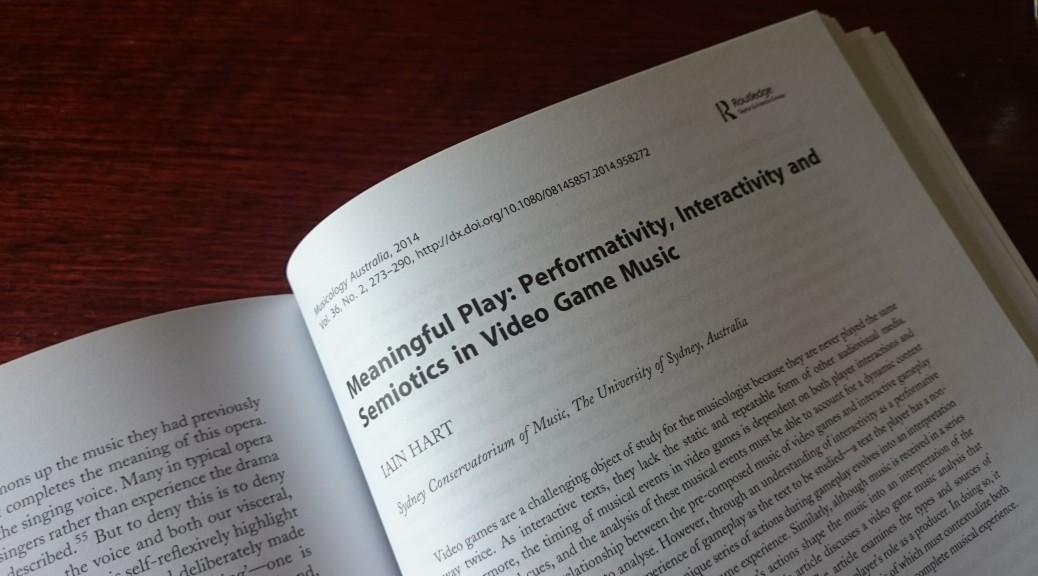

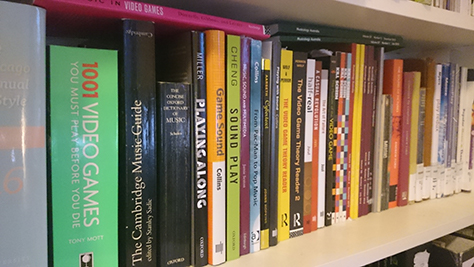

Lo-fi information storage and communication devices

There are three kinds of books: 1. books that tell you stuff, 2. books that tell you stuff that isn’t real, and 3. books where you tell them the stuff. All of these smell better that computers and only require a source of light to be usable (and in case 3, a writing implement). So, in the inevitable event that one of the various proposed apocalypses occurs and worldwide electricity grids go down, you can still complete your PhD on video games the old-school way. Except for the case study chapters. And now with more of a historical than a theoretical flavour. And with a near-crippling suspicion that you’re wasting your life and should probably be out gathering resources (which may or may not be standard anyway).

Productivity gain: Can enable your thesis work to proceed post-apocalypse. At least until you get eaten by a zombie because you were reading and not running — reverts to an interminable state of procrastination at that point

Procrastination gain: You could read a thousand books a day for 100 years and still not get through all the books in the world. Go nuts.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save